April 13, 2017

Research

Ohio State University | April 13 2017

A new nationwide study has found that children entering first grade in 2013 had significantly better reading skills than similar students had just 12 years earlier.

Researchers say this means that in general, children are better readers at a younger age, but the study also revealed where gaps remain -- especially in more advanced reading skills.

The good news was that even low-achieving students saw gains in basic reading skills over this time period and actually narrowed the achievement gap with other young readers.

However, that didn't translate into better overall reading for the less-skilled children. The research showed that the gap between low-achieving readers and others actually widened when it came to advanced reading skills.

"Overall, it is good news," said Jerome D'Agostino, co-author of the study and professor of educational studies at The Ohio State University.

"We have evidence that the increased emphasis on learning important skills earlier in life is having a real impact on helping develop reading abilities by first grade."

But the results also show that strategies to help preschoolers who are having trouble with language skills need to be adjusted, said co-author Emily Rodgers, associate professor of teaching and learning at Ohio State.

"We're probably spending too much time emphasizing basic skills for the low-achieving students, when we should be giving them more opportunities to actually read text," she said.

Their study is published in the current issue of the journal Educational Researcher.

The study involved 2,358 schools from 44 states. A total of 364,738 children were assessed during the 12 years of the study. This included 313,488 low-achieving students who were selected to participate in Reading Recovery, a literacy intervention for first-grade students. Another 51,250 randomly selected students from the same schools also participated.

All children were tested at the beginning of first grade, before the Reading Recovery students began their intervention program.

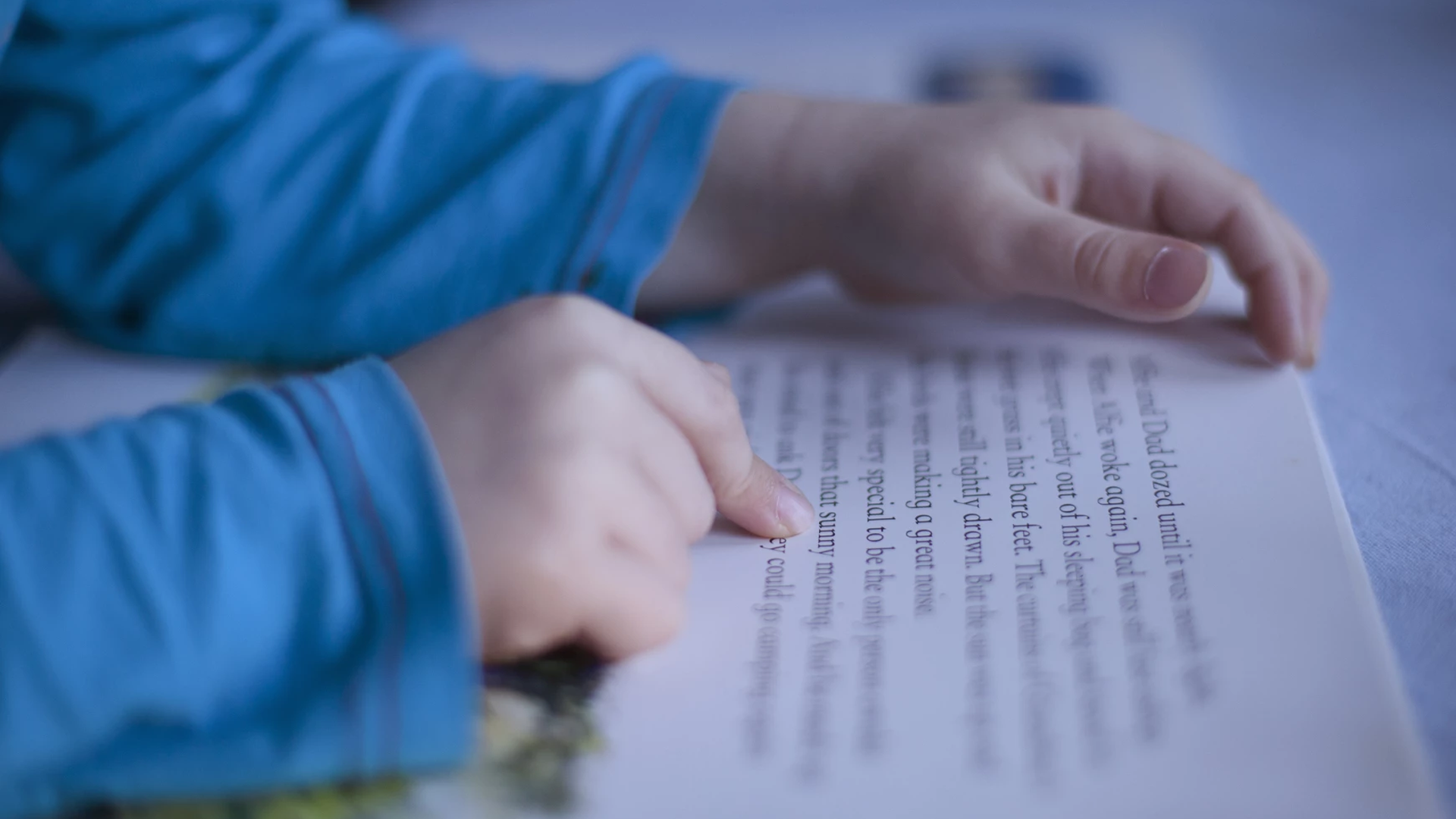

Students took a screening test called An Observation Survey of Early Literacy Achievement. The survey measures four basic skills (letter identification, word recognition, ability to identify and use sounds and print awareness), as well as two advanced skills (writing vocabulary and text reading).

The results showed that average scores on all six parts of the test increased over the 12 years, suggesting that many children end kindergarten with the skills they used to learn in first grade.

"Children are better prepared when they enter first grade than they used to be. Kindergarten is the new first grade when it comes to learning reading skills," Rodgers said.

In the four basic skills, low-achieving students narrowed the achievement gap with other readers. But in the two advanced skills -- including actually reading text -- the gap widened.

This data can't say why that is, D'Agostino said.

"There's a missing link between teaching low-achieving students basic literacy skills and having them actually put those skills to use in reading," he said. "We don't know what that is yet."

However, he noted that while poorer readers did reduce the achievement gap in basics skills, the gap was still sizable.

"We're getting the low-achievement students only part of the way there," Rodgers said. "They're doing better at learning sounds and letters and now we have to do a better job helping them put it all together and read text."

Why have reading scores for entering first-graders improved since 2002?

D'Agostino and Rodgers said that two influential national reports released in the 2000s (the National Reading Panel in 2000 and the National Early Literacy Panel in 2008) urged changes in reading instruction.

Both of those reports, as well as the No Child Left Behind law, led to an increased emphasis on learning important skills related to reading achievement in preschool and kindergarten, the researchers said.

"Those reports and legislation had at least some of the desired effect," D'Agostino said. "But now we need to make sure that low-achieving students don't fall further behind."

Originally published on OSU.edu.