May 23, 2023

State Strategies

It’s no surprise that school attendance is significantly related to student achievement, including third grade reading and high school graduation. Too many absences can keep a student from learning and advancing in school.

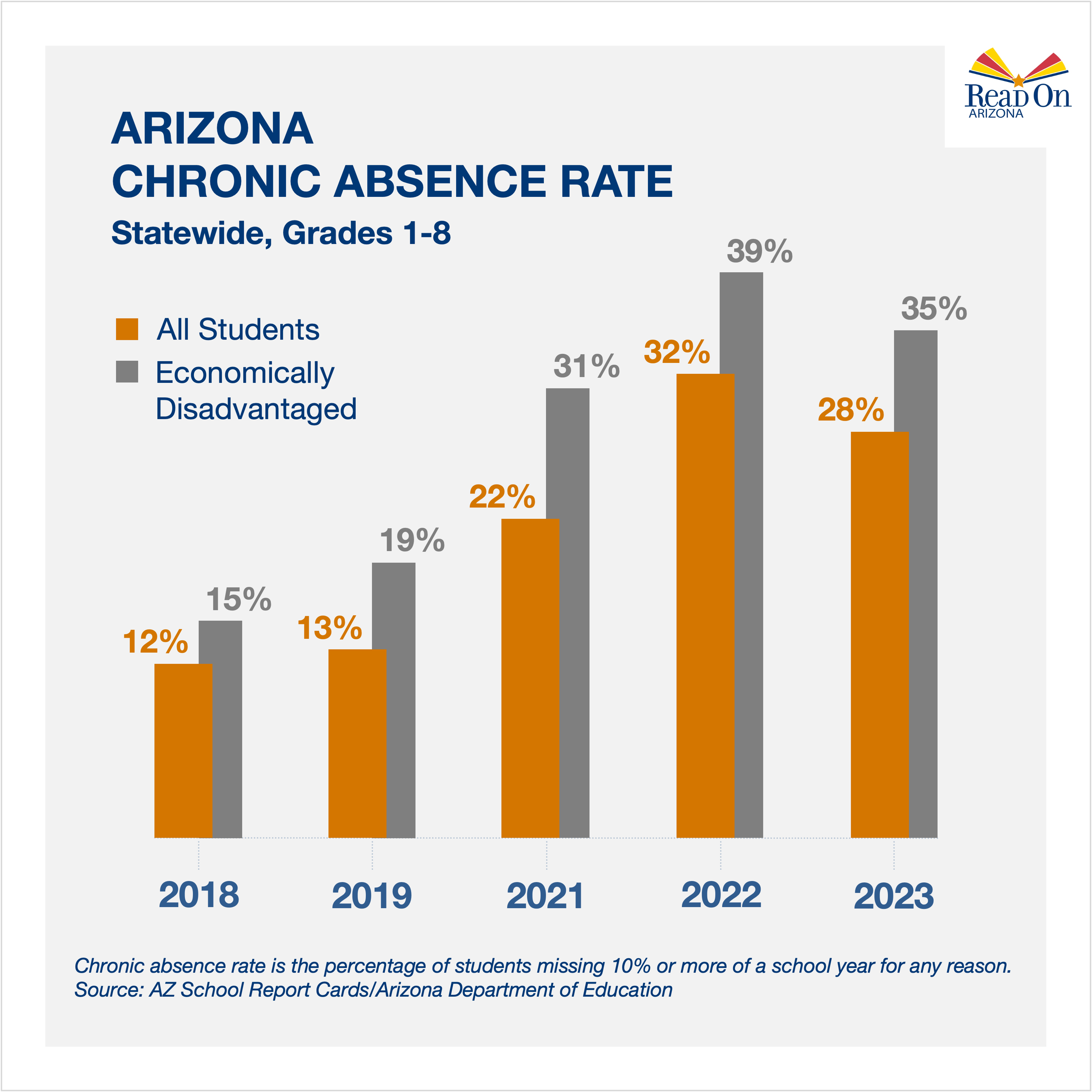

A student is considered chronically absent when they miss 10% or more of a school’s calendar year for any reason, excused or unexcused. That’s about 18 days or more in a typical school year.

Chronic absence has always been an issue, but recent data from the Arizona Department of Education shows a dramatic, post-pandemic spike in the rate of chronic absence in Arizona’s public schools:

Across Grades 1-8, 32% of Arizona students were identified as chronically absent in 2022, up from 13% in 2019.

Chronic absence rates were even higher among economically disadvantaged students and Native American students.

These statistics are alarming, but there are evidence-based solutions to tackle chronic absence. Solutions that work. And policies and practices that prevent absences also produce increases in early literacy outcomes. Analysis of Arizona school-level data showed that a 1% increase in school-level attendance rate was associated with a 1.5% increase in students passing Arizona’s third grade reading assessment.

"When we put our heads together, we can find solutions and bring them to scale."

Arizona Chronic Absence Task Force

Leaders from the Governor’s office, school districts, state agencies, community partners, legislative staff, and education stakeholders have begun to review data and confer with national experts from Attendance Works. Over the next year, the group will develop recommendations and resources focused on prevention and re-engaging students and families.

Dr. Betsy Hargrove, superintendent of the Avondale Elementary School District, sees the task force as an opportunity for collaboration that will benefit students and schools in her district and across Arizona.

“We’ve had success with chronic absence,” said Dr. Hargrove, “and it’s important to keep learning and share what’s working with leaders from across the state. When we put our heads together, we can find solutions and bring them to scale. And with Read On Arizona’s leadership, you know it’s going to be meaningful and productive.”

The Issue

Students miss school for many different reasons. Challenges may include the lack of consistent housing or transportation, which is a common barrier in rural communities. Family circumstances, illness, or trauma can be involved. Some students may be struggling or disengaged, with no meaningful relationships to adults in the school. Every circumstance is different and often complex.

Hedy Chang, executive director of Attendance Works, helped frame the issue in the first meeting of the task force.

“Chronic absence is different from truancy, which only counts unexcused absences,” she said. “Effective approaches to chronic absence cultivate student and family engagement, so that families and students are not problems to be solved but are active in designing the solutions.”

Dr. Lenay Dunn of WestEd reinforced this approach: “We need a mindset shift from accountability to supports and solutions.”

To amplify these efforts, Read On Arizona has secured funding for Attendance Works to provide training for Arizona educators to learn effective, evidence-based strategies to promote attendance and engagement and support students using a team approach that mobilizes school staff and community partners. Cohorts will be formed later this year for e-learning series to begin in Fall 2023 and Spring 2024.

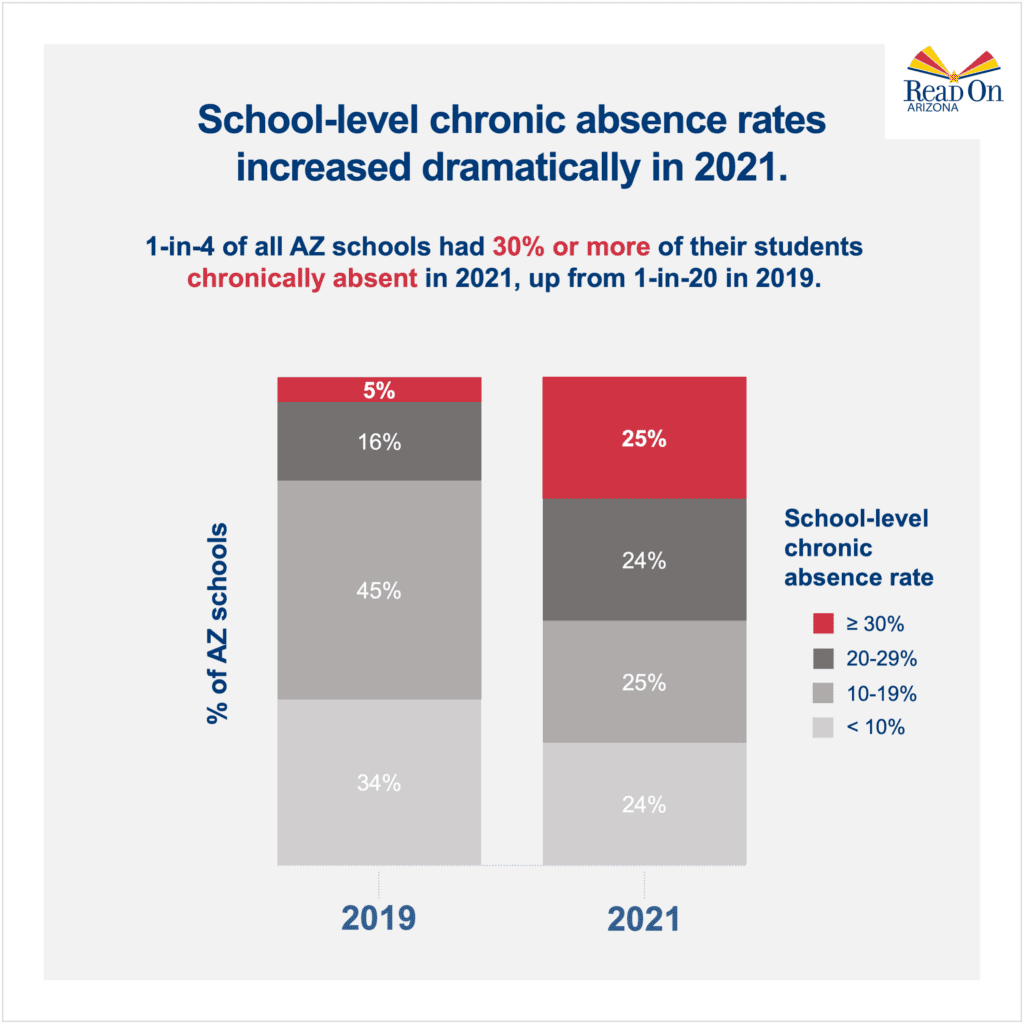

More Schools Facing More Absences

Chronic absence is not a new phenomenon, but in the wake of the pandemic, the scale of the problem has grown exponentially. In 2019, five percent of Arizona schools had chronic absence rates of 30% or more. In 2021, that number quintupled; a quarter of all public schools in Arizona saw a large percentage of their students miss numerous school days.

Window Rock, on the Navajo Nation, illustrates how chronic absence is a multifaceted issue with factors that are unique to each community.

COVID-19 cases and deaths were exponentially higher on the Navajo Nation than other areas of the state.

“Many of the deaths were among the elders who also served as primary caregivers of children,” said Dr. Shannon Goodsell, superintendent of Window Rock Unified School District. “As a result, many children moved in with another part of their family.”

“We also have approximately 200 students that we haven’t seen since COVID. ‘Ghost children.’ They were with the district prior to the pandemic and have not shown up in other districts, BIA schools, charter schools, online schools, or for homeschooling.”