DeMiguel Elementary School

DeMiguel Elementary School

Flagstaff Unified School District | Flagstaff, Arizona

Arizona public and charter school students in grades 3-8 take annual grade-level assessment tests in English Language Arts (ELA) and Mathematics. The ELA test encompasses reading, comprehension, language, and writing and serves as our state’s benchmark for third grade reading proficiency, which research shows to be a strong predictor of future academic success.

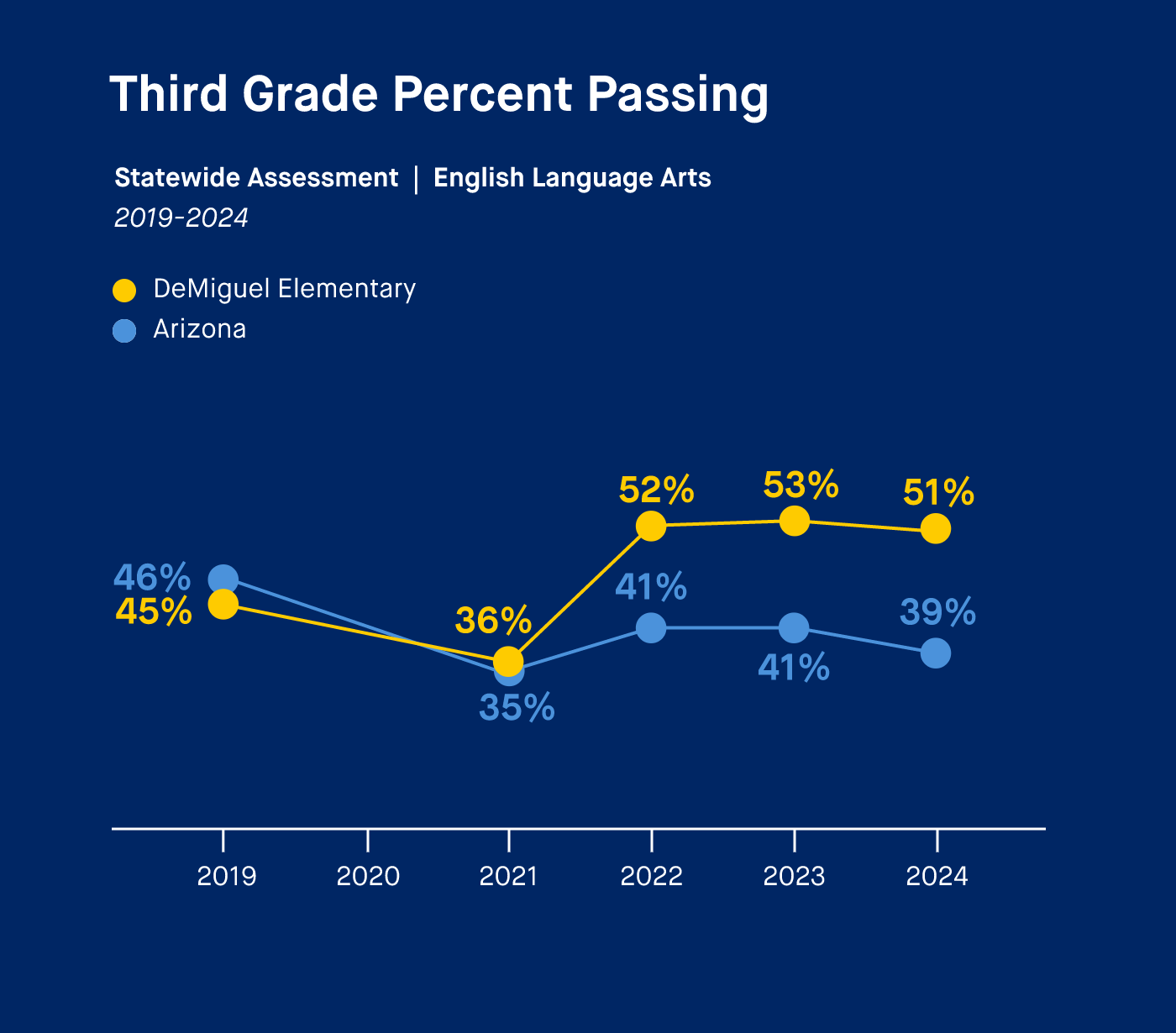

Third graders at DeMiguel Elementary School in Flagstaff have been outperforming the statewide average for third grade ELA scores over the past few years:

- 51% of DeMiguel’s third graders scored in the proficient and highly proficient levels in 2024.

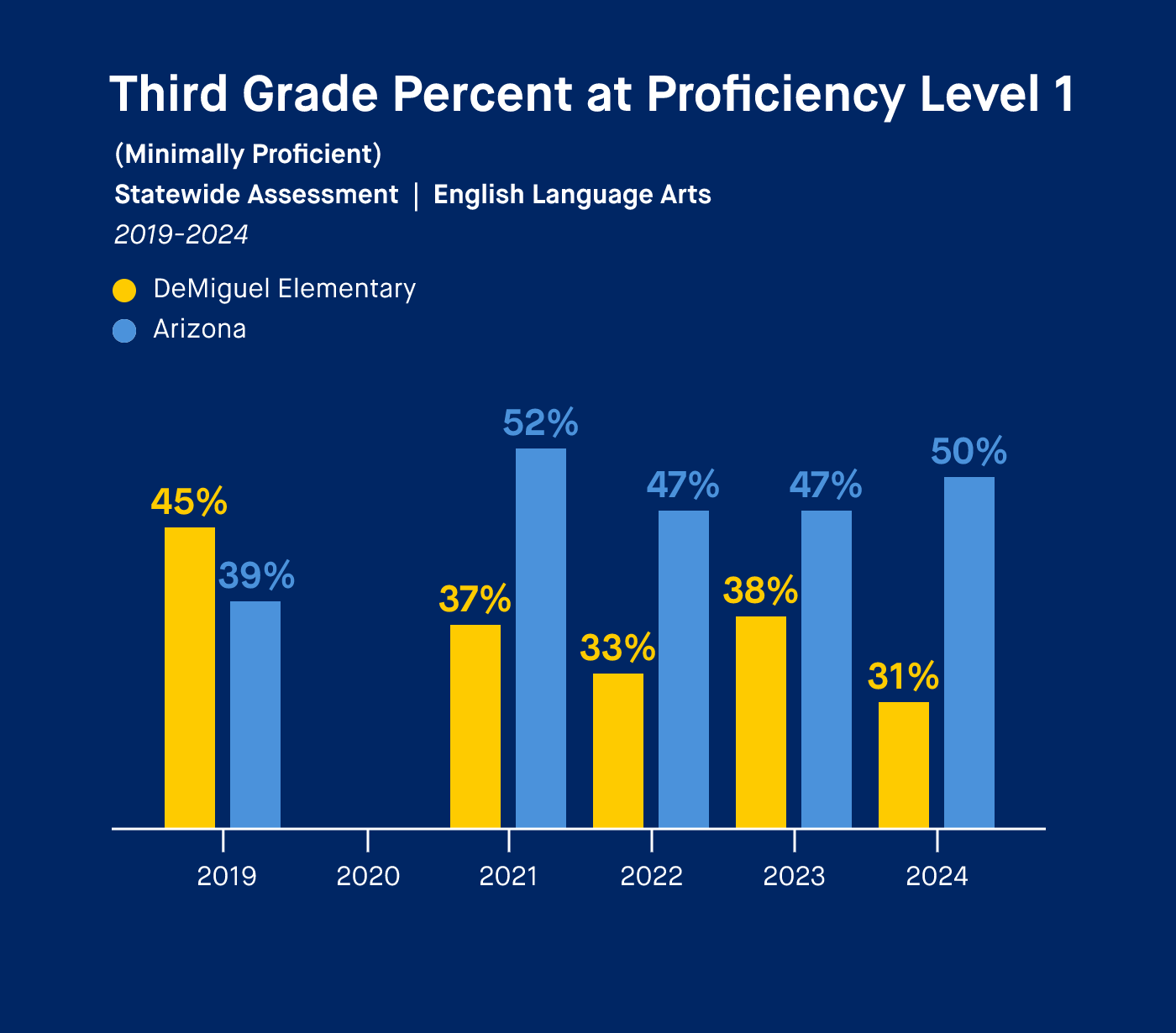

- The school’s percentage of third graders scoring in the lowest proficiency category (level 1/minimally proficient) has decreased significantly since the pandemic.

Educators at DeMiguel attribute their students’ success to several key factors:

- Focusing on student data to target instruction.

- Using evidence-based programs to build foundational skills.

- Training teachers in the science of reading.

- Building strong relationships with families.

What key factors drove DeMiguel’s success?

DeMiguel Elementary School is part of the Flagstaff Unified School District. In recent years, the district has been implementing several new strategies to increase third grade reading proficiency, including evidence-based reading curricula, skills-based supplemental programs, and educator training in the science of reading.

Read On Arizona met with several of DeMiguel’s educators to learn about the school’s approach to literacy in the early grades:

- Joy Bruner, First Grade Teacher

- Rachel Merriman, Kindergarten Teacher

- Nancy Pierce, District Literacy Coach

- Todd Rossman, Program Specialist

- Katie Warke, Instructional Specialist

- Focusing on student data to target instruction.

"It starts with using our data," said Katie Warke, DeMiguel’s instructional specialist.

Screeners help identify students who aren’t "at target, and from there, we use additional screeners, things like phonic surveys or phonemic awareness screeners, to pinpoint where the holes are for those students." Students with common needs are grouped together for interventions and progress monitored weekly or bi-weekly.

"As a team, we’ve started using more screeners up front," said first grade teacher Joy Bruner. "Staff can see gaps in students' literacy skills and use data to make small groups and target those specific areas of need."

"That’s been huge," said Rachel Merriman, who teaches kindergarten at DeMiguel. "If you look for where a student is missing a skill, and then you focus (instruction) on that skill, then they rise."

In recent years, literacy data has become a central topic in weekly grade-level professional learning communities (PLCs), "whether from benchmarking or from screeners collected in the classroom or formative assessments that we use along the way, to measure how students are doing with their growth towards standards," Warke said.

"If you look for where a student is missing a skill, and then you focus on that skill, then they rise."

"We're talking about our observations of the students and what we’re seeing as a whole," Merriman said, "and what we can do to address any of the concerns we might have."

"Because of the curriculum and the data that we collect, we’re really able to fine tune the program for the kids," said Todd Rossman, DeMiguel’s program specialist for special education and gifted education.

- Using evidence-based programs to build foundational skills.

DeMiguel uses the district-approved Reach for Reading (ESSA evidence rating: strong) as its curriculum for Tier 1 instruction. The school has also added research-based supplemental programs focused on phonics and phonemic awareness to bolster core reading instruction and Tier 2 interventions.

"We started using the 95 Phonics Core Program" as a supplement to Tier 1," Warke said. "All students get that."

The school’s focus on building foundational literacy skills through explicit instruction starts in kindergarten and continues through the early grades.

"All of our kindergarten and first grade classes are working strongly in phonemic awareness," said Nancy Pierce, Flagstaff Unified’s district literacy coach. "That’s the base-level building block."

"We’ve seen a lot of success based on that," Merriman said. "Kids knowing and listening for sounds a lot more, and understanding the sounds connected to the letters. It's been huge. It's been a big, big change."

"And then we build on with phonics, layering on the decoding piece," Pierce said. "And that builds by grade level, so when we hit third grade, we’re getting more into the morphology of words, breaking down multi-syllable words, to be able to attack them and also know what those words mean."

"All of our kindergarten and first grade classes are working strongly in phonemic awareness."

The school adjusted its schedule to reflect students’ needs for targeted interventions.

"Coming back from Covid times, and seeing how many gaps there were and the holes that we had to fill, we realized the importance of having that intervention time be consistent and sticking to the schedule," Warke said.

Each grade level is scheduled for intervention time during a different window of the day, which maximizes the number of skilled interventionists available to support students.

"We call it What I Need (WIN) time. It’s a Walk to Read model. And so basically all of our students at the grade level are put into small groups" for an additional 30 minutes, four days a week, "for everything from intensive intervention to enrichment."

The model also works well for special education students.

"Kids aren’t being pulled out during core reading instruction or 95 Phonics," said Todd Rossman, DeMiguel’s program specialist for special education. "We always personalize special education for each student, but for the majority of our students who are dealing with a learning disability and or other issue with reading, that 30 minutes, four days a week works well. It also allows the special education team time, on that fifth day, to go into classrooms and support kids that way, as well."

- Training teachers in the science of reading.

Educators at DeMiguel have taken advantage of professional development opportunities provided by the Flagstaff Unified School District, in partnership with Coconino County Education Service Agency, and the Arizona Department of Education to build their understanding of the science of reading.

"We've had a lot of teachers going through LETRS training," Warke said. "I think teachers are naturally people who want to continue to learn and do better." Implementing that learning "has made a big difference" in Tier 1 instruction and small group interventions. "It’s made teachers feel more powerful with their reading instruction."

"When I went through (LETRS) volume one and volume two, that was a complete game changer," Bruner said. "It has definitely changed my whole outlook on teaching reading."

"Learning about how the brain makes the connections for reading has helped us understand why students may not be making progress in certain areas," Rossman said.

"It has definitely changed my whole outlook on teaching reading."

Teaching practices have changed to align with the science of reading, and outdated practices, such as cueing, are no longer being used.

"We also have Nancy at the district who will come over and model a lesson for us," Warke said. "That coaching really helps them put their new learning, their new training, into practice directly in the classroom."

Pierce and Bruner also facilitate LETRS training for teachers. "Seeing the light bulbs go off has been really amazing," Bruner said.

"You feel like you know why you’re doing what you’re doing," Merriman said.

"It also enables us to give that 'why' to parents," Rossman said.

The school recently revamped its outdated kindergarten development assessment, which includes information for parents about the phases of literacy and writing development, to align with the science of reading.

"Now it matches what we’re doing in kindergarten," Merriman said. "Parents look at that progression now and know what to expect. That parent support at home is huge."

- Building strong relationships with families.

The educators at DeMiguel emphasized the importance of family engagement and letting families know how they can help support their child’s learning at home.

"We hold our relationships with our families sacred," Merriman said. "It’s so important that they have the right information and know what's going on" so they can reinforce what’s happening in the classroom. "We work really hard to keep them in the loop."

"With our special education students, that’s one of the most important parts to our student success, that family involvement," Rossman said. "That makes all the difference in the world."

"We hold our relationships with our families as sacred."

Because of the staff’s understanding of the science of reading, "we’re able to have deeper conversations with families and help them understand why their students may be having reading difficulties," Rossman said.

The heart of the school's success are the relationships staff build with students.

"Showing true interest in what they’re all about, taking time each day to recognize each individual learner," Rossman said, "I think we’re really strong at that here at DeMiguel."