April 05, 2018

Literacy News

Seventy. That’s the percentage of fourth graders in Arizona who don’t read proficiently.

If that isn’t alarming enough, a whopping 56 percent of third-graders failed the reading portion of the AzMERIT test in 2017, meaning they scored neither proficient nor highly proficient.

According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress, 65 percent of fourth-graders nationwide don’t read proficiently, compared to 70 percent in Arizona. NAEP defines “proficient” as “competency of challenging subject matter.”

The 65 percentage point hasn’t changed much. It isn’t much of an improvement since 1992, when the percentage was 71.

The Arizona Department of Education found that students who don’t read proficiently by third grade are four times more likely to drop out of high school, and that 90 percent of high school dropouts struggled with reading in third grade.

Statistics show that 32 million adults in the United States are illiterate — about 13 percent of all U.S. adults. In 2003, Tucson-based organization Literacy Connects reported that 530,000 adults in Arizona read at or below a fifth-grade reading level.

And despite many recent initiatives to improve reading skills across the country, the problem remains. Why aren’t children reading at levels they should?

Poverty could be one reason. Nearly 7 in 10 third-graders from low-income families failed the AzMERIT in 2015. And according to the Annie E. Casey Foundation, 80 percent of fourth-graders from low-income families don’t read proficiently.

Put simply, these children don’t have books. Many families can’t afford them. Erika Nichols-Frazer, the communications manager for the Children’s Literacy Foundation, said on average there is only one book for every 300 children in low-income communities.

Besides affordability, Nichols-Frazer said that many parents might be too busy juggling multiple jobs to visit the library or read to their child daily.

Additionally, parents of low-income families are often unable to afford early childcare. Specifically, the Annie E. Casey Foundation said that 62 percent of children ages 3 to 4 in Arizona were not enrolled in preschool in 2016.

“Those who have attended preschool come to kindergarten more prepared,” Nichols-Frazer said. “They’ve read books, they’ve talked to other kids. Free childcare is a huge issue.”

Free childcare is nearly nonexistent in Arizona. In 2017, Tucson residents voted on Proposition 204, an initiative to pay for early childhood education. The proposition failed. And even though poverty is a giant issue among literacy rates, the Children’s Literacy Foundation says 2 in 5 children in high-income families are not read to daily, either. Research shows that the more you read to children, the better their literacy levels and comprehension will be.

Sometimes the K-12 education system is to blame. In which case, Arizona ranks dangerously low.

Teachers often don’t have the funds to afford books to facilitate better reading lessons. Budget cuts don’t make anything better.

“Many districts don’t have money to buy books,” said David Paige, associate professor of education at Bellarmine University. “A good teacher can take limited materials and figure out how to make them work. But they would be able to do a lot better if they had more of the right materials.”

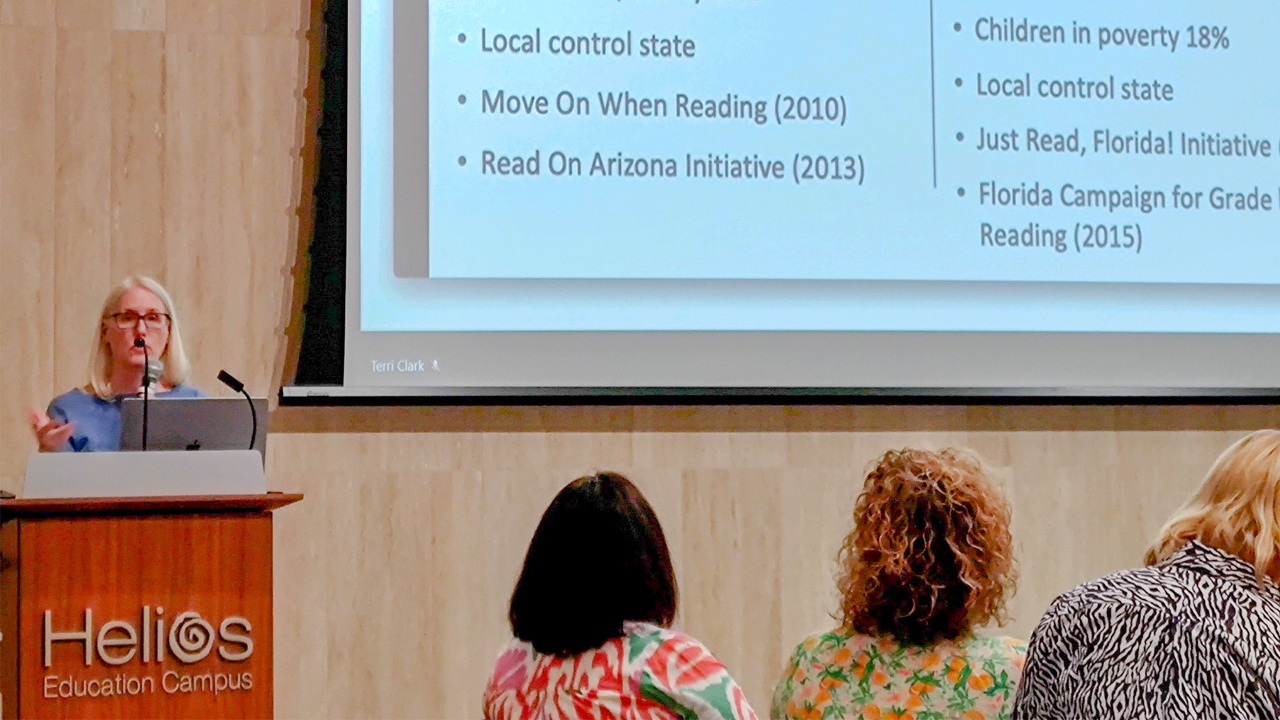

Terri Clark, literacy director of Read On Arizona, agreed, stating that “dangerous cuts” have been made to the education system in Arizona.

“It’s like, we’re asked to build a house, but we’re only given the bare minimum to build it,” Clark said.

But Paige said that even in high-income schools, some students still don’t read proficiently. He says one of the ways to change that is better curriculum.

Paige co-wrote a study in 2012. In it, he found that high school students who can read fluently aloud tend to read proficiently overall. His research showed that curriculum can be altered to better cater to students’ needs and help them connect to the literature.

For example, if classrooms incorporated literature with a strong voice, such as plays, students’ fluency would improve, thus improving their comprehension of the content and reading skills overall.

Another reading initiative in Arizona, the “Move On When Reading” legislation, was passed in 2010 and enacted in 2013. According to the Arizona Department of Education, third-graders who perform “far below the third grade level” in the reading section of the AzMERIT, in addition to other factors such as quarterly benchmarks, should not be promoted to fourth grade. This is said to provide students with extra time to pick up on needed literacy skills.

Exceptions are made for students learning English and students diagnosed with a learning impairment or disability.

Despite the startling number of third-graders who failed last year’s AzMERIT test, 842 students of the 87,164 who took the exam were not promoted to fourth grade. This is only 1 percent of all third-graders—even though 56 percent failed the end-of-year exam.

“There is no silver-bullet answer to improving literacy,” Clark said. “It’s making sure every child has access and opportunities.”

Beyond K-12 education, Paige said, “We don’t do a very good job at teaching college students how to teach reading.”

Clark agreed. She said that aspiring teachers are often only taught the very basics of how to teach reading. But if a child is having a hard time reading due to a disability, a teacher might not have the background to “support that struggling reader.”

School principals are not always trained in reading, either, especially if they previously taught science or another unrelated subject, which doesn’t help the literacy problem.

There’s also the belief that the strict push for standardized testing handcuffs teachers’ ability to teach reading.

“We make tests such high stakes for kids,” said Timothy Rasinski, professor of literacy education at Kent State University. “If students don’t pass these tests, they’re supposed to be retained. Teachers often, and understandably so, focus on teaching to the test rather than teaching kids how to read.”

Although poverty and the education system can be partly to blame, improving the literacy rate can be as easy as picking up an object and saying its name aloud to your young child. It’s as easy as reading to your child 20 minutes a day and having them read aloud 20 minutes a day when they’re old enough to do so.

Nichols-Frazer also said that when parents weren’t read to as kids, or if they don’t feel comfortable with their own literacy skills, they might not want to read to their children. She says it’s time to break that cycle.

Nichols-Frazer said there could also be a lack of awareness regarding when to start reading — which should begin as soon as humanly possible.

“Studies show that children who have heard language and vocabulary in the womb are able to form better literacy skills,” Nichols-Frazer said.

Research also has shown a slew of little fixes throughout the years. In 2016, 91 percent of children said they were more likely to read if they picked out the book themselves, according to Nichols-Frazer.

“There is no silver-bullet answer to improving literacy,” Clark said. “It’s making sure every child has access and opportunities.”